Part I: Orientation

1.1 What is ChESS?

ChESS (Chess-board Extraction by Subtraction and Summation) is a classical, ID‑free detector for chessboard X‑junction corners. It is designed specifically for grid‑like calibration targets: black–white checkerboards, Charuco‑style boards, and other high‑contrast grids where four alternating quadrants meet at each corner.

Unlike generic corner detectors (Harris, Shi–Tomasi, FAST, etc.), ChESS is tuned to answer the question:

“Is this pixel the intersection of a checkerboard grid?”

It does this by sampling a 16‑point ring around each candidate pixel and combining two kinds of evidence:

- A “square” term that compares opposite quadrants on the ring, rewarding alternating dark/bright quadrants.

- A “difference” term that penalizes edge‑like structures where intensity flips but doesn’t form an X‑junction.

- A consistency term that compares the ring mean to a 5‑pixel cross at the center, discouraging isolated blobs.

These ingredients are combined into a single ChESS response value per pixel. Strong positive responses correspond to chessboard‑like corners; everything else is suppressed by thresholding, non-maximum suppression, and a small cluster filter. A 5×5 refinement step is then used to estimate a subpixel corner position.

Typical use cases:

- Camera calibration (mono or stereo), where you want robust chessboard corners across a variety of lighting conditions and slight blur.

- Pose estimation of calibration rigs and fixtures.

- Robotics and AR setups where chessboards are used as temporary alignment targets.

Compared to other approaches:

- Versus generic corner detectors: ChESS is more selective and produces fewer false corners on edges, blobs, or texture; it is specialized but more reliable when you know you’re looking at a chessboard.

- Versus ID‑based markers (AprilTags, ArUco): ChESS detects unlabeled grid corners; there is no embedded ID and no global pattern decoding. That can be an advantage when you already know the pattern layout (e.g., an 8×6 checkerboard) and just need accurate corners.

The chess-corners-rs workspace implements ChESS in Rust with an emphasis on clarity, testability, and high performance (scalar, rayon, and portable SIMD paths), plus ergonomic wrappers for common Rust image workflows.

If you are reading this book online via GitHub Pages, the generated Rust API docs for the crates are also available:

chess-corners-coreAPI reference: see/chess_corners_core/chess-cornersAPI reference: see/chess_corners/

1.2 Project layout

This repository is a small Rust workspace with two main library crates and a CLI:

-

chess-corners-core– low-level core- Path:

crates/chess-corners-core - Responsibilities:

- Compute dense ChESS response maps on 8‑bit grayscale images (

responsemodule). - Run the detector pipeline on a response map (

detectmodule): thresholding, NMS, cluster filtering, subpixel refinement. - Define the core types:

ChessParams– tunable parameters for the response and detector (ring radius, thresholds, NMS radius, minimum cluster size).ResponseMap– a simplew × hVec<f32>wrapper for the response.CornerDescriptor– a rich corner description with subpixel position, response, and orientation.

- Stay lean and portable:

no_stdis supported when thestdfeature is disabled.

- Compute dense ChESS response maps on 8‑bit grayscale images (

- Intended audience:

- Users who need maximum control, want to integrate with custom image types, or want to experiment with the ChESS math and detector pipeline directly.

- Path:

-

chess-corners– ergonomic facade- Path:

crates/chess-corners - Responsibilities:

- Re-export core types (

ChessParams,CornerDescriptor,ResponseMap) so you can usually depend on this crate alone. - Provide a high-level detector configuration:

ChessConfig– combinesChessParamswith multiscale tuning (CoarseToFineParams).

- Implement single-scale and multiscale detection:

find_chess_corners_image– detect corners from animage::GrayImage(when theimagefeature is enabled).find_chess_corners_u8– detect corners directly from&[u8]buffers.- Multiscale internals (

multiscalemodule):CoarseToFineParams– pyramid + ROI + merge tuning.find_chess_corners_buff/find_chess_corners– coarse‑to‑fine detector using image pyramids.

- Pyramid internals (

pyramidmodule):ImageView,ImageBuffer– minimal grayscale image view and buffer.PyramidParams,PyramidBuffers,build_pyramid– reusable image pyramid construction with optional SIMD/rayonvia thepar_pyramidfeature.

- Optionally ship a CLI binary for batch runs and visualization.

- Re-export core types (

- Intended audience:

- Users who want “just detect chessboard corners” in a Rust image pipeline with minimal boilerplate.

- Users who want multiscale detection and performance tuning without touching the lowest-level core types.

- Path:

-

chess-cornersCLI – command-line tool- Path:

crates/chess-corners/bin - Entrypoints:

bin/main.rs,bin/commands.rs,bin/logger.rs

- Responsibilities:

- Load images and optional config JSON (

config/chess_cli_config_example.json). - Run single-scale or multiscale detection using the library API.

- Emit JSON summaries of detected corners and visualization PNG overlays.

- Optionally emit JSON tracing spans for profiling.

- Load images and optional config JSON (

- Intended audience:

- Quick experiments and debugging.

- Pipeline testing without writing Rust code (e.g., from scripts).

- Path:

There are also supporting directories:

config/– example configs for the CLI.testdata/– sample images used in tests / experiments.tools/– helper scripts such asplot_corners.pyfor overlay visualization.

1.3 Installing and enabling features

1.3.1 As a library dependency

The easiest way to use ChESS from your own project is to depend on the chess-corners facade crate. In your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

chess-corners = "0.3.1"

image = "0.25" # if you want GrayImage integration

This gives you:

- High-level

ChessConfig/ChessParams. find_chess_corners_imageforimage::GrayImage.find_chess_corners_u8for raw&[u8]buffers.- Access to

CornerDescriptorandResponseMap.

A minimal single‑scale example with image:

use chess_corners::{ChessConfig, ChessParams, find_chess_corners_image};

use image::io::Reader as ImageReader;

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let img = ImageReader::open("board.png")?

.decode()?

.to_luma8();

let mut cfg = ChessConfig::single_scale();

cfg.params = ChessParams::default();

let corners = find_chess_corners_image(&img, &cfg);

println!("found {} corners", corners.len());

Ok(())

}If you don’t use image, you can work directly with raw buffers:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use chess_corners::{ChessConfig, ChessParams, find_chess_corners_u8};

fn detect(img: &[u8], width: u32, height: u32) {

let mut cfg = ChessConfig::single_scale();

cfg.params = ChessParams::default();

let corners = find_chess_corners_u8(img, width, height, &cfg);

println!("found {} corners", corners.len());

}

}For very advanced use cases (custom image layout, special ROI handling, or integrating your own detector stages), you can depend on chess-corners-core directly instead and work with response / detect modules.

1.3.2 Feature flags and performance

Both crates use Cargo features to control performance and diagnostics:

-

On

chess-corners-core:std(default) – enable standard library usage. Disable forno_std+alloc.rayon– parallelize response computation over rows.simd– enable portable SIMD for the response kernel (requires nightly).tracing– addtracingspans to response / descriptor paths.

-

On

chess-corners:image(default) – enableimage::GrayImageintegration and the image-based helpers.rayon– forwardrayonto the core and parallelize multiscale refinement. Combine withpar_pyramidto parallelize pyramid downsampling.simd– forwardsimdto the core and enable SIMD on the response path (nightly). Combine withpar_pyramidfor SIMD downsampling.par_pyramid– opt-in gate for SIMD/rayonacceleration inside the pyramid builder.tracing– enable tracing in the core and multiscale layers.ml-refiner– enable the ONNX-backed ML subpixel refiner entry points.cli– build thechess-cornersbinary.

In your own Cargo.toml, you can opt into specific combinations:

[dependencies]

chess-corners = { version = "0.3", features = ["image", "rayon"] }

For example:

- Default, single-threaded (simplest): no extra features beyond

image. - Multi-core scalar: add

"rayon"to accelerate response/refinement on multi-core machines; add"par_pyramid"as well to parallelize downsampling. - SIMD-accelerated: enable

"simd"(and use a nightly compiler) to vectorize the inner loops; add"par_pyramid"to apply SIMD to pyramid downsampling too. - Tracing-enabled: enable

"tracing"and run withRUST_LOG/tracing-subscriberto capture spans.

All combinations are designed to produce the same numerical results; features only affect performance and observability.

1.3.3 Building and using the CLI

If you’re working inside this workspace, you can build and run the CLI directly:

cargo run -p chess-corners --release --bin chess-corners -- \

run config/chess_cli_config_example.json

This will:

- Load the image specified in the config.

- Run single-scale or multiscale detection depending on the

pyramid_levelsandmin_sizesettings (withpyramid_levels <= 1behaving as single-scale). - Save JSON output with detected corners and optional PNG overlays.

You can treat the CLI as:

- A quick way to sanity‑check your installation.

- A reference implementation of how to wire up the library APIs.

- A convenient debugging/profiling harness when you tweak configuration or features.

This orientation part should give you enough context to know what ChESS is, how this workspace is structured, and how to bring the detector into your own project. In the next parts, we can dive deeper into the core ChESS math, the multiscale implementation, and practical tuning strategies.

Part II: Using the Detector

In Part I we oriented ourselves in the project and saw the high‑level

building blocks: the ChESS response, the detector pipeline, and the

chess-corners facade crate. In this part we focus entirely on

using the detector in practice.

We start with the simplest way to get corners out of an image using

the image crate, then show how to work directly with raw grayscale

buffers, and finally look at the bundled CLI for quick experiments and

batch processing.

2.1 Single-scale detection with image

The easiest way to use ChESS is through the chess-corners facade

crate, together with the image crate’s GrayImage type.

Make sure your Cargo.toml has:

[dependencies]

chess-corners = "0.3.1"

image = "0.25"

The image feature on chess-corners is enabled by default, so you

get convenient helpers on image::GrayImage without any extra work.

2.1.1 Minimal example

Here is a complete single‑scale example:

use chess_corners::{ChessConfig, ChessParams, find_chess_corners_image};

use image::io::Reader as ImageReader;

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// 1. Load a grayscale image.

let img = ImageReader::open("board.png")?

.decode()?

.to_luma8();

// 2. Start from a single-scale configuration.

let cfg = ChessConfig::single_scale();

// 3. Run the detector.

let corners = find_chess_corners_image(&img, &cfg);

println!("found {} corners", corners.len());

Ok(())

}The key pieces are:

ChessConfig::single_scale()– configures a single‑scale detector by settingmultiscale.pyramid.num_levels = 1.ChessParams::default()– provides reasonable defaults for the ChESS response and detector (ring radius, thresholds, NMS radius, minimum cluster size).find_chess_corners_image– runs the detector on aGrayImageand returns aVec<CornerDescriptor>.

2.1.2 Inspecting detected corners

Each corner is described by a CornerDescriptor re‑exported from the

core crate. You can inspect the fields like this:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

for c in &corners {

println!(

"corner at ({:.2}, {:.2}), response {:.1}, theta {:.2} rad",

c.x, c.y, c.response, c.orientation,

);

}

}Important details:

x,y– subpixel coordinates in full‑resolution image pixels, using the usual(0,0)top‑left origin andxto the right,ydown.response– the ChESS response at this location. Larger positive values mean the local structure looks more like an ideal chessboard corner.orientation– orientation of one of the grid axes in radians, in[0, π). The other axis is atorientation + π/2.

For basic camera calibration workflows you can often treat response

as a confidence score and use orientation mainly for grid fitting

or downstream topology checks.

2.1.3 Tweaking ChessParams

The default ChessParams values are tuned to work well on typical

calibration images, but it is useful to know what they do:

use_radius10– switch from the canonical r=5 ring to a larger r=10 ring, which is more robust under heavy blur or when the board covers fewer pixels.threshold_rel/threshold_abs– control how strong a response must be to be considered a candidate corner. Ifthreshold_absisSome, it takes precedence overthreshold_rel; otherwise a relative threshold (fraction of the maximum response) is used.nms_radius– radius of the non‑maximum suppression window in pixels. Larger values give sparser corners.min_cluster_size– minimum number of positive‑response neighbors in the NMS window required to accept a corner, which suppresses isolated noise.

Small threshold_rel and nms_radius values tend to produce more

corners (including weaker or spurious ones), while larger values

produce fewer, stronger corners. It’s often helpful to log or plot the

detected corners on your own images and adjust these parameters once

per dataset.

2.2 Raw buffer API

The image integration is convenient, but you may already have image

data in another form (camera SDK, FFI, GPU pipeline). In those cases

you can bypass image entirely and work directly with &[u8]

buffers.

2.2.1 find_chess_corners_u8

The chess-corners crate exposes:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub fn find_chess_corners_u8(

img: &[u8],

width: u32,

height: u32,

cfg: &ChessConfig,

) -> Vec<CornerDescriptor>;

}Requirements:

imgmust be a contiguouswidth * heightslice in row‑major order.- Pixels are 8‑bit grayscale (

0= black,255= white).

Usage is nearly identical to the image‑based helper:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use chess_corners::{ChessConfig, ChessParams, find_chess_corners_u8};

fn detect(img: &[u8], width: u32, height: u32) {

let mut cfg = ChessConfig::single_scale();

cfg.params = ChessParams::default();

let corners = find_chess_corners_u8(img, width, height, &cfg);

println!("found {} corners", corners.len());

}

}Internally, this constructs an ImageView over the buffer and calls

the same multiscale machinery as the image helper, so results are

identical for the same configuration.

2.2.2 Custom buffers and strides

If your buffers are not tightly packed (e.g., you have a stride or interleaved RGB data), you will need to adapt them before calling the detector:

- For RGB/RGBA images, convert to grayscale first (e.g., using your

own kernel or via

imagewhen convenient), then callfind_chess_corners_u8on the luminance buffer. - For images with a stride, either:

- copy each row into a temporary tightly‑packed buffer and reuse it per frame, or

- construct your own

ResponseMapusingchess-corners-coreand a custom sampling function that respects the stride (covered in later parts of the book).

The simplest path is usually:

- Convert to a packed grayscale buffer once.

- Reuse it across calls to

find_chess_corners_u8.

2.2.3 ML refiner (feature ml-refiner)

The ML refiner is an optional ONNX-backed subpixel refinement stage.

Enable it by turning on the ml-refiner feature and calling the ML

entry points:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use chess_corners::{ChessConfig, find_chess_corners_image_with_ml};

use image::GrayImage;

let img = GrayImage::new(1, 1);

let cfg = ChessConfig::default();

let corners = find_chess_corners_image_with_ml(&img, &cfg);

}The ML refiner runs an ONNX model on normalized patches (uint8 / 255.0) and

predicts [dx, dy, conf_logit]. The current version ignores the confidence

output and applies the offsets directly, using the embedded model defaults.

2.3 CLI workflows

The workspace includes a chess-corners binary that wraps the library

APIs with configuration, image I/O, and basic visualization. It lives

under crates/chess-corners/bin and is built when the cli feature

is enabled in this crate.

2.3.1 Basic usage

From the workspace root, you can run:

cargo run -p chess-corners --release --bin chess-corners -- \

run config/chess_cli_config_example.json

This will:

- Load the image specified in the

imagefield of the config. - Decide between single‑scale and multiscale based on

pyramid_levels(if> 1, multiscale is used). - Run the detector with the configured parameters.

- Write a JSON file with detected corners and, by default, a PNG overlay image with small white squares drawn at corner positions.

The exact fields are defined by DetectionConfig in

crates/chess-corners/bin/commands.rs. The example config under

config/ documents common settings:

pyramid_levels,min_size,refinement_radius,merge_radius– multiscale controls (mapped ontoCoarseToFineParams; withpyramid_levels <= 1the detector behaves as single‑scale, and larger values request a coarse‑to‑fine multiscale run, bounded bymin_size).threshold_rel,threshold_abs,refiner,radius10,descriptor_radius10,nms_radius,min_cluster_size– detector tuning (mapped ontoChessParams;refineracceptscenter_of_mass,forstner, orsaddle_pointand uses default settings for each choice).ml– settrueto enable the ML refiner pipeline (requires theml-refinerfeature).output_json,output_png– output paths; when omitted, defaults are derived from the image filename.

You can override many of these fields with CLI flags; the CLI uses

DetectionConfig as a base and then applies overrides.

2.3.2 ML refiner from the CLI

The CLI switches to the ML pipeline when ml is true in

the JSON config. You must also build the binary with the

ml-refiner feature:

cargo run -p chess-corners --release --features ml-refiner --bin chess-corners -- \

run config/chess_cli_config_example_ml.json

The ML configuration is currently a boolean toggle; the refiner uses the embedded model defaults and ignores the confidence output.

2.3.3 Inspecting results

The CLI produces:

- A JSON file containing:

- basic metadata (image path, width, height),

- the multiscale configuration actually used (

pyramid_levels,min_size,refinement_radius,merge_radius), and - an array of corners with

x,y,response, andorientation.

- A PNG image with the detected corners drawn as small white squares over the original image.

You can:

- Load the JSON in Python, Rust, or any other language and feed the detected corners into your calibration / pose estimation tools.

- Use the PNG overlay for quick visual validation of parameter choices.

Combined with the configuration file, this makes it easy to iterate on

detector settings without recompiling your code. Once you are happy

with a configuration, you can port the settings into your own Rust

code using ChessConfig, ChessParams, and CoarseToFineParams.

2.3.4 Example overlays

Running the CLI on the sample images in testdata/ produces overlays like these:

2.4 Python bindings

The workspace ships a PyO3-based Python extension in

crates/chess-corners-py, published as the chess_corners package.

It exposes the same detector with a NumPy-friendly API.

Install (from PyPI):

python -m pip install chess-corners

Basic usage:

import numpy as np

import chess_corners

img = np.zeros((128, 128), dtype=np.uint8)

corners = chess_corners.find_chess_corners(img)

print(corners.shape, corners.dtype) # (N, 4), float32

find_chess_corners expects a 2D uint8 array (H, W) and returns a

float32 array with columns [x, y, response, orientation]. For

configuration, create ChessConfig() and set fields such as

threshold_rel, nms_radius, pyramid_num_levels, and

merge_radius. See crates/chess-corners-py/README.md for a full

parameter reference.

If the bindings are built with the ml-refiner feature, you can call

find_chess_corners_with_ml in Python as well. The ML path uses the

embedded model defaults and is slower but can improve subpixel

precision on synthetic data.

In this part we focused on the public faces of the detector: the

image helper, the raw buffer API, the CLI, and the Python bindings.

In the next parts we will look under the hood at how the ChESS

response is computed, how the detector turns responses into subpixel

corners, and how the multiscale pipeline is structured.

Part III: Core ChESS Internals

In this part we leave the ergonomic chess-corners facade and look at

the lower‑level chess-corners-core crate. This crate is responsible

for:

- defining the ChESS rings and sampling geometry,

- computing dense response maps on 8‑bit grayscale images,

- turning responses into corner candidates with NMS and refinement,

- converting raw candidates into rich corner descriptors.

The public API is intentionally small and stable; feature flags (std,

rayon, simd, tracing) only affect performance and observability,

not the numerical results.

3.1 Rings and sampling geometry

The ChESS response is built around a fixed 16‑sample ring at a

given radius. The core crate encodes these rings in

crates/chess-corners-core/src/ring.rs.

3.1.1 Canonical rings

The main types are:

RingOffsets– an enum representing the supported ring radii (R5andR10).RING5/RING10– the actual offset tables for radius 5 and 10.ring_offsets(radius: u32)– helper returning the offset table for a given radius (anything other than 10 maps to 5).

The 16 offsets are ordered clockwise starting at the top, and are derived from the FAST‑16 pattern:

RING5is the canonicalr = 5ring used in the original ChESS paper.RING10is a scaled variant (r = 10) with the same angles, which improves robustness under heavier blur at the cost of a larger footprint and border margin.

The exact offsets are stored as integer (dx, dy) pairs, so sampling

around a pixel (x, y) means accessing (x + dx, y + dy) for each

ring point.

3.1.2 From parameters to rings

ChessParams in lib.rs controls which ring to use:

use_radius10– whentrue,ring_radius()returns 10 instead of 5.descriptor_use_radius10– optional override specifically for the descriptor ring; whenNone, it followsuse_radius10.

Convenience methods:

ring_radius()/descriptor_ring_radius()return the numeric radii.ring()/descriptor_ring()returnRingOffsetsvalues, which can be turned into offset tables viaoffsets().

The response path uses ring(), while descriptor estimation uses

descriptor_ring(). This allows you, for example, to detect corners

with a smaller ring but compute descriptors on a larger one.

3.2 Dense response computation

The main entry point in response.rs is:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub fn chess_response_u8(img: &[u8], w: usize, h: usize, params: &ChessParams) -> ResponseMap

}This function computes the ChESS response at each pixel center whose full ring fits entirely inside the image. Pixels that cannot support a full ring (near the border) get response zero.

3.2.1 ChESS formula

For each pixel center c, we gather 16 ring samples s[0..16) using

the offsets described in §3.1, and a small 5‑pixel cross at the

center:

- center

c, - north/south/east/west neighbors.

From these values we compute:

-

SR– a “square” term that compares opposite quadrants on the ring:SR = sum_{k=0..3} | (s[k] + s[k+8]) - (s[k+4] + s[k+12]) | -

DR– a “difference” term encouraging edge‑like structure:DR = sum_{k=0..7} | s[k] - s[k+8] | -

μₙ– the mean of all 16 ring samples. -

μₗ– the local mean of the 5‑pixel cross.

The final ChESS response is:

R = SR - DR - 16 * |μₙ - μₗ|

Intuitively:

SRis large when opposite quadrants have contrasting intensities (as in an X‑junction).DRis large for simple edges, and subtracting it de‑emphasizes edge‑like structures.|μₙ - μₗ|penalizes isolated blobs or local illumination changes.

High positive values of R correspond to chessboard‑like corners.

3.2.2 Implementation paths and borders

chess_response_u8 is implemented in a few interchangeable ways:

- Scalar sequential path (

compute_response_sequential/compute_row_range_scalar) – a straightforward nested loop over rows and columns. - Parallel path (

compute_response_parallel) – when therayonfeature is enabled, the outer loop is split across threads usingpar_chunks_mutover rows. - SIMD path (

compute_row_range_simd) – when thesimdfeature is enabled, the inner loop vectorizes overLANESpixels at a time, using portable SIMD to gather ring samples and accumulateSR,DR, andμₙin vector registers.

Regardless of the path, the function:

- respects a border margin equal to the ring radius so that all ring accesses are in bounds,

- writes responses into a

ResponseMap { w, h, data }in row‑major order, - guarantees that the scalar, parallel, and SIMD variants produce the same numerical result up to small floating‑point differences.

3.2.3 ROI support with Roi

For multiscale refinement, we rarely need the response over the entire image. Instead we compute it inside small regions of interest around coarse corner predictions.

The Roi struct:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub struct Roi {

pub x0: usize,

pub y0: usize,

pub x1: usize,

pub y1: usize,

}

}describes an axis‑aligned rectangle in image coordinates. A specialized function:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub fn chess_response_u8_patch(

img: &[u8],

w: usize,

h: usize,

params: &ChessParams,

roi: Roi,

) -> ResponseMap

}computes a response map only inside that ROI, treating the ROI as a small image with its own (0,0) origin. This is used in the multiscale pipeline to refine coarse corners without paying the cost of full‑frame response computation at the base resolution.

3.3 Detection pipeline

The response map is only the first half of the detector. The second

half—implemented in detect.rs—turns responses into subpixel corner

candidates.

3.3.1 Thresholding and NMS

The main stages are:

- Thresholding – we reject responses that are too small to be

meaningful:

- either via a relative threshold (

threshold_rel) expressed as a fraction of the maximum response in the image, - or via an absolute threshold (

threshold_abs), when provided.

- either via a relative threshold (

- Non‑maximum suppression (NMS) – in a window of radius

nms_radiusaround each pixel, we keep only local maxima and suppress weaker neighbors. - Cluster filtering – we require that each surviving corner have

at least

min_cluster_sizepositive‑response neighbors in its NMS window. This discards isolated noisy peaks that don’t belong to a structured corner.

The result of this stage is a set of raw corner candidates, each carrying:

- integer‑like peak position,

- response strength (before refinement).

3.3.2 Subpixel refinement

To reach subpixel accuracy, the detector runs a 5×5 refinement step around each candidate:

- a small window is extracted around the integer peak,

- local gradients / intensities are analyzed to estimate a more precise corner position,

- the refined position is stored as

(x, y)in floating‑point form.

The internal type representing these refined candidates is

descriptor::Corner:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub struct Corner {

/// Subpixel location in image coordinates (x, y).

pub xy: [f32; 2],

/// Raw ChESS response at the integer peak (before COM refinement).

pub strength: f32,

}

}The refinement logic is designed to preserve the detector’s noise robustness while giving more precise coordinates for downstream tasks like calibration.

3.4 Corner descriptors

Raw corners (position + strength) are enough for many applications,

but the core crate also offers a richer CornerDescriptor type that

includes an estimated corner orientation.

3.4.1 CornerDescriptor

Defined in descriptor.rs:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub struct CornerDescriptor {

pub x: f32,

pub y: f32,

pub response: f32,

pub orientation: f32,

}

}Fields:

x,y– subpixel coordinates in full‑resolution image pixels.response– ChESS response at the corner, copied fromCorner.orientation– orientation of the corner — defined as the direction along the bisector of the light square — in radians, constrained to[0, π).

3.4.2 From corners to descriptors

The function:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub fn corners_to_descriptors(

img: &[u8],

w: usize,

h: usize,

radius: u32,

corners: Vec<Corner>,

) -> Vec<CornerDescriptor>

}turns raw Corner values into full descriptors by:

- Sampling the ring around each corner using bilinear interpolation

(

sample_ring). - Estimating orientation from the ring samples

(

estimate_orientation_from_ring). This essentially measures a second‑harmonic over the ring’s angular positions to find the dominant grid axis.

All these steps are deterministic, local computations on the original grayscale image and its immediate neighborhood.

3.4.3 When to use descriptors

You get CornerDescriptor values when you use the high‑level APIs:

chess-corners-coreusers can run the response and detector stages manually and then callcorners_to_descriptors.chess-cornersusers getVec<CornerDescriptor>directly from helpers such asfind_chess_corners_image,find_chess_corners_u8, or the multiscale APIs.

For many tasks, you might only use x, y, and response. When you

need more insight into local structure (for example, fitting a grid or

doing downstream topology checks), the orientation estimate can be

useful.

In this part we dissected the chess-corners-core crate: how rings

and sampling geometry are defined, how the dense ChESS response is

computed, how the detector turns responses into subpixel candidates,

and how those candidates are enriched into descriptors. In the next

part we will build on this by examining the multiscale pyramids and

coarse‑to‑fine refinement pipeline in more detail.

Part IV: Multiscale and Pyramids

In Parts II and III we treated the detector mostly as a single‑scale operation: run ChESS on an image and get back corners. In practice, however, real‑world images often vary in scale and blur. A chessboard might occupy just a small region of a large frame, or it might be far from the camera so the corner pattern is heavily blurred.

To handle these cases efficiently and robustly, the chess-corners

crate offers a coarse‑to‑fine multiscale detector built on top of

simple image pyramids. This part describes:

- how the pyramid utilities work,

- how the coarse‑to‑fine detector uses them,

- how to choose multiscale configurations in practice.

4.1 Image pyramids

The multiscale code lives in crates/chess-corners/src/pyramid.rs.

It implements a minimal grayscale pyramid builder tuned for the

detector’s needs: no color, no arbitrary scaling; just fixed 2×

downsampling with optional SIMD/rayon acceleration when

par_pyramid is enabled.

4.1.1 Image views and buffers

Two basic types represent images:

-

ImageView<'a>– a borrowed view:#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct ImageView<'a> { pub width: u32, pub height: u32, pub data: &'a [u8], } }from_u8_slice(width, height, data)validates thatwidth * height == data.len()and returns a view on success.- With the

imagefeature,ImageViewcan also be constructed directly fromimage::GrayImageviaFrom<&GrayImage>.

-

ImageBuffer– an owned buffer:#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct ImageBuffer { pub width: u32, pub height: u32, pub data: Vec<u8>, } }It is used as backing storage for pyramid levels and exposes

as_view()to obtain anImageView<'_>.

These types keep the pyramid code decoupled from any particular image

crate while remaining easy to integrate when image is enabled.

4.1.2 Pyramid structures and parameters

An image pyramid is represented as:

-

PyramidLevel<'a>– a single level with:#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct PyramidLevel<'a> { pub img: ImageView<'a>, pub scale: f32, // relative to base (e.g. 1.0, 0.5, 0.25, ...) } } -

Pyramid<'a>– a top‑down collection wherelevels[0]is always the base image (scale 1.0), and subsequent levels are downsampled copies:#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct Pyramid<'a> { pub levels: Vec<PyramidLevel<'a>>, } }

The shape of the pyramid is controlled by:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub struct PyramidParams {

pub num_levels: u8,

pub min_size: u32,

}

}num_levels– maximum number of levels (including the base).min_size– smallest allowed dimension (width or height) for any level; once a level would fall below this size, construction stops.

The default is num_levels = 1, min_size = 128. If you need to speed up ceature detection, try num_levels = 2 or num_levels = 3.

4.1.3 Reusable buffers

To avoid frequent allocations, PyramidBuffers holds the owned

buffers for non‑base levels:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub struct PyramidBuffers {

levels: Vec<ImageBuffer>,

}

}Typical usage:

- Construct a

PyramidBuffersonce, often usingPyramidBuffers::with_capacity(num_levels)to pre‑reserve space. - For each frame, call the pyramid builder with a base

ImageViewand the same buffers. The code automatically resizes or reuses internal buffers as needed.

The high‑level multiscale API (find_chess_corners) creates and

manages its own PyramidBuffers internally, but the lower‑level

find_chess_corners_buff entry point lets you supply your own

buffers, which is useful in tight real‑time loops.

4.1.4 Building the pyramid

The core builder is:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub fn build_pyramid<'a>(

base: ImageView<'a>,

params: &PyramidParams,

buffers: &'a mut PyramidBuffers,

) -> Pyramid<'a>

}It always includes the base image as level 0, then repeatedly:

- halves the width and height (integer division by 2),

- checks against

min_sizeandnum_levels, - ensures the appropriate buffer exists in

PyramidBuffers, - calls

downsample_2x_boxto fill the next level.

If num_levels == 0 or the base image is already smaller than

min_size, the function returns an empty pyramid.

4.1.5 Downsampling and feature combinations

The downsampling kernel is a simple 2×2 box filter:

- for each output pixel, average the corresponding 2×2 block in the source image (with a small rounding tweak to keep values in 0–255),

- write the result into the next level’s

ImageBuffer.

Depending on features:

- without

par_pyramid, downsampling always uses the scalar single-thread path even ifrayon/simdare enabled elsewhere. - with

par_pyramidbut norayon/simd,downsample_2x_box_scalarruns in a single thread. - with

par_pyramid+simd,downsample_2x_box_simduses portable SIMD to process multiple pixels at once. - with

par_pyramid+rayon,downsample_2x_box_parallel_scalarsplits work over rows; with bothrayonandsimd,downsample_2x_box_parallel_simdcombines row-level parallelism with SIMD inner loops.

As with the core ChESS response, all paths are designed to produce identical results except for small rounding differences; they only differ in performance.

4.2 Coarse-to-fine detection

The multiscale detector is implemented in

crates/chess-corners/src/multiscale.rs. Its job is to:

- optionally build a pyramid from the base image,

- run the ChESS detector on the smallest level to find coarse corner candidates,

- refine each coarse corner back in the base image using small ROIs,

- merge near‑duplicate refined corners,

- convert them into

CornerDescriptorvalues in base‑image coordinates.

4.2.1 Coarse-to-fine parameters

The main configuration structure is:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub struct CoarseToFineParams {

pub pyramid: PyramidParams,

/// ROI radius at the coarse level (ignored when num_levels <= 1).

pub refinement_radius: u32,

pub merge_radius: f32,

}

}pyramid– controls how many levels are built and how small the smallest level is allowed to be.refinement_radius– radius of the ROI around each coarse corner in the coarse‑level pixels; internally converted to a base‑level radius using the pyramid scale.merge_radius– radius in base‑image coordinates used to merge near‑duplicate refined corners (i.e., corners that end up within a small distance of each other).

CoarseToFineParams::default() provides a reasonable starting point:

- 3 pyramid levels with minimum size 128,

- ROI radius 3 at the coarse level (scaled up at the base; with 3 levels this is ≈12 px at full resolution),

- merge radius 3.0 pixels.

4.2.2 The find_chess_corners_buff workflow

The main multiscale function is:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub fn find_chess_corners_buff(

base: ImageView<'_>,

cfg: &ChessConfig,

buffers: &mut PyramidBuffers,

) -> Vec<CornerDescriptor>

}It proceeds in several steps:

- Build the pyramid using

cfg.multiscale.pyramidand the providedbuffers.- If the resulting pyramid is empty (e.g., base too small), return an empty corner set.

- Single‑scale special case – if the pyramid has only one level:

- run

chess_response_u8on the base level, - run the detector on the response to get raw

Cornervalues, - convert them with

corners_to_descriptors, - return descriptors directly.

- run

- Coarse detection:

- take the smallest level in the pyramid (

pyramid.levels.last()), - run

chess_response_u8and the detector to get coarseCornercandidates at the coarse scale. - if no coarse corners are found, return an empty set.

- take the smallest level in the pyramid (

- ROI definition and refinement:

- compute the inverse scale

inv_scale = 1.0 / coarse_lvl.scale, - for each coarse corner:

- map its coordinates up to base image space,

- skip corners too close to the base image border (to keep enough room for the ring and refinement window),

- convert

cfg.multiscale.refinement_radiusfrom coarse pixels to base pixels, enforcing a minimum based on the detector’s border requirements, - clamp the ROI to keep it entirely within safe bounds,

- compute

chess_response_u8_patchinside this ROI, - rerun the detector on the patch response to get finer

Cornercandidates, - shift patch coordinates back into base‑image coordinates.

- gather all refined corners.

- compute the inverse scale

- Merging and describing:

- run

merge_corners_simplewithmerge_radiusto combine refined corners whose positions are withinmerge_radiusof each other, keeping the stronger one. - convert merged

Cornervalues intoCornerDescriptors usingcorners_to_descriptorswithparams.descriptor_ring_radius().

- run

When the rayon feature is enabled, the refinement step can process

coarse corners in parallel; otherwise it uses a straightforward loop.

4.2.3 Convenience wrapper: find_chess_corners

For many applications it’s enough to let the library manage the pyramid buffers:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub fn find_chess_corners(

base: ImageView<'_>,

cfg: &ChessConfig,

) -> Vec<CornerDescriptor>

}This helper:

- constructs a

PyramidBufferswith capacity forcfg.multiscale.pyramid.num_levels, - calls

find_chess_corners_buff, - returns the resulting descriptors.

It is the internal entry point behind:

find_chess_corners_image(forimage::GrayImage), andfind_chess_corners_u8(for raw&[u8]buffers).

Use find_chess_corners_buff when you want to reuse buffers across

frames; use the higher‑level helpers when you prefer simplicity over

fine‑grained control.

4.3 Choosing multiscale configs

The behavior of the multiscale detector is driven primarily by

CoarseToFineParams:

pyramid.num_levels,pyramid.min_size,refinement_radius,merge_radius.

Here are some practical guidelines and starting points.

4.3.1 Single-scale vs multiscale

-

Single-scale:

- Set

pyramid.num_levels = 1. - The detector behaves exactly like the single‑scale path: it runs ChESS once at the base resolution and skips coarse refinement.

- This is a good choice when:

- the chessboard occupies a large portion of the frame,

- the board is reasonably sharp, and

- you want maximum recall at a fixed scale.

- Set

-

Multiscale:

- Use

pyramid.num_levelsin the range 2–4 for most use cases. - More levels mean:

- coarser initial detection (smaller image yields fewer, more robust coarse corners),

- more refinement work at the base level,

- potentially better robustness when the board is small or heavily blurred.

- Use

As a rule of thumb, start with num_levels = 3 and adjust only if you

have specific performance or robustness requirements.

4.3.2 min_size and pyramid coverage

pyramid.min_size limits how small the smallest level can be. If the

base image is small (e.g., smaller than min_size), the pyramid may

end up with a single level regardless of num_levels, effectively

falling back to single‑scale.

Recommendations:

- Choose

min_sizeso that the smallest level still has a few pixels per square on the chessboard. If your board is already small in the base image, a too‑aggressivemin_sizemay collapse the pyramid and give you no coarse‑to‑fine benefit. - For high‑resolution inputs (e.g., 4K), a

min_sizearound 128 or 256 usually works well.

4.3.3 ROI radius

refinement_radius is specified in coarse‑level pixels and converted to

base‑level pixels using the pyramid scale. Internally, the code also

enforces a minimum ROI radius that respects:

- the ChESS ring radius,

- the NMS radius,

- the 5×5 refinement window.

Larger ROIs:

- cost more to process (bigger patches),

- can recover from slightly off coarse positions,

- may pick up nearby corners if multiple corners are close together.

Smaller ROIs:

- are faster,

- assume coarse positions are already fairly accurate.

The default refinement_radius = 3 is a reasonable compromise. Increase it

if you see coarse corners that consistently refine to the wrong

locations; decrease it if performance is tight and coarse positions

are already good.

4.3.4 Merge radius

merge_radius controls the distance (in base pixels) used to merge

refined corners. If two corners fall within this radius of each other,

only the stronger one is kept.

Guidelines:

- For typical calibration boards, values around 1.5–2.5 pixels are common.

- If your detector tends to produce duplicate corners around the same

junction (e.g., because the ROI refinement finds multiple close

maxima), increase

merge_radius. - If you need to preserve nearby but distinct corners (e.g., very fine grids), consider decreasing it slightly.

4.3.5 Putting it together

Some example presets:

-

Default multiscale (good starting point):

num_levels = 3min_size = 128–256refinement_radius = 3merge_radius = 3.0

-

Fast single-scale:

num_levels = 1min_sizeignored (no pyramid)refinement_radius/merge_radiusunused

-

Robust small‑board detection:

num_levels = 3–4min_sizetuned so the smallest level still has a handful of pixels per square (e.g., 64–128)refinement_radiusslightly larger (e.g., 4–5)merge_radiusaround 2.0–3.0

Once you’ve chosen parameters that work well for your dataset, you can

encode them in your ChessConfig for library use or in a CLI config

JSON for batch experiments.

In this part we explored the multiscale machinery in chess-corners:

the minimal pyramid builder, the coarse‑to‑fine detector, and how to

choose multiscale parameters. In the next part we will look at

performance considerations, tracing, and how to integrate the detector

into larger systems while measuring and tuning its behavior.

Part V: Performance, Accuracy, and Integration

This part summarizes where the ChESS detector stands today on accuracy and speed (measured on a MacBook Pro M4), how well it matches classic OpenCV detectors on a stereo calibration dataset, how to interpret the traces we emit, and how to integrate the detector into larger pipelines.

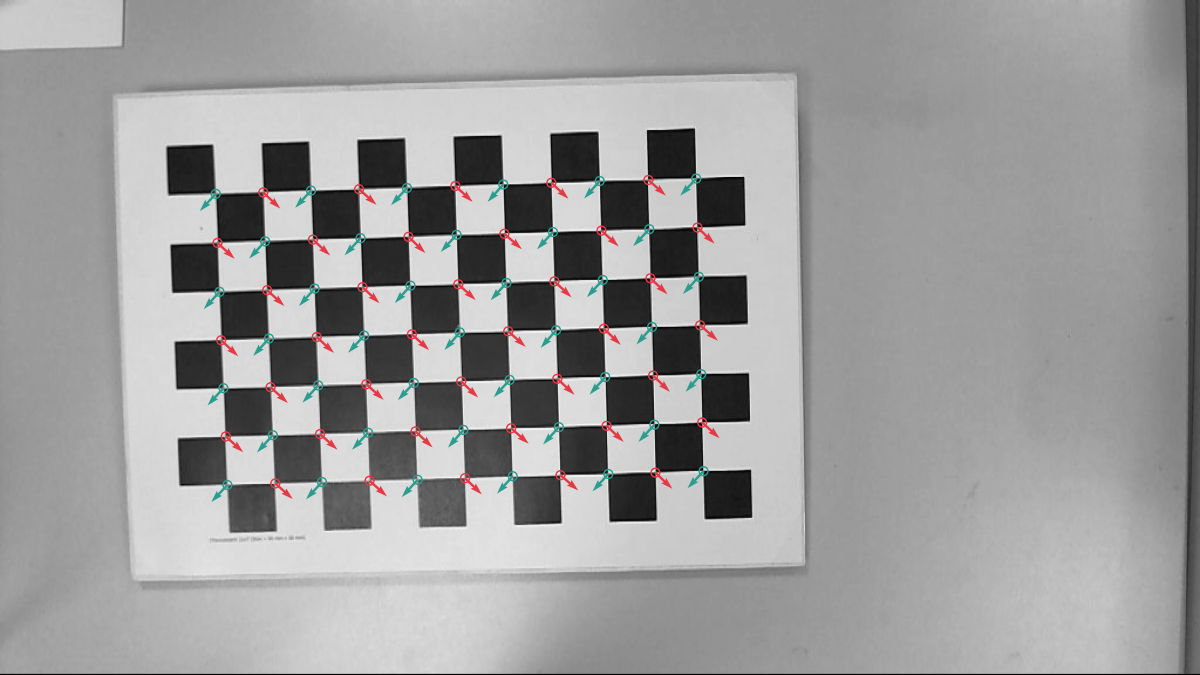

We took three test images as use cases:

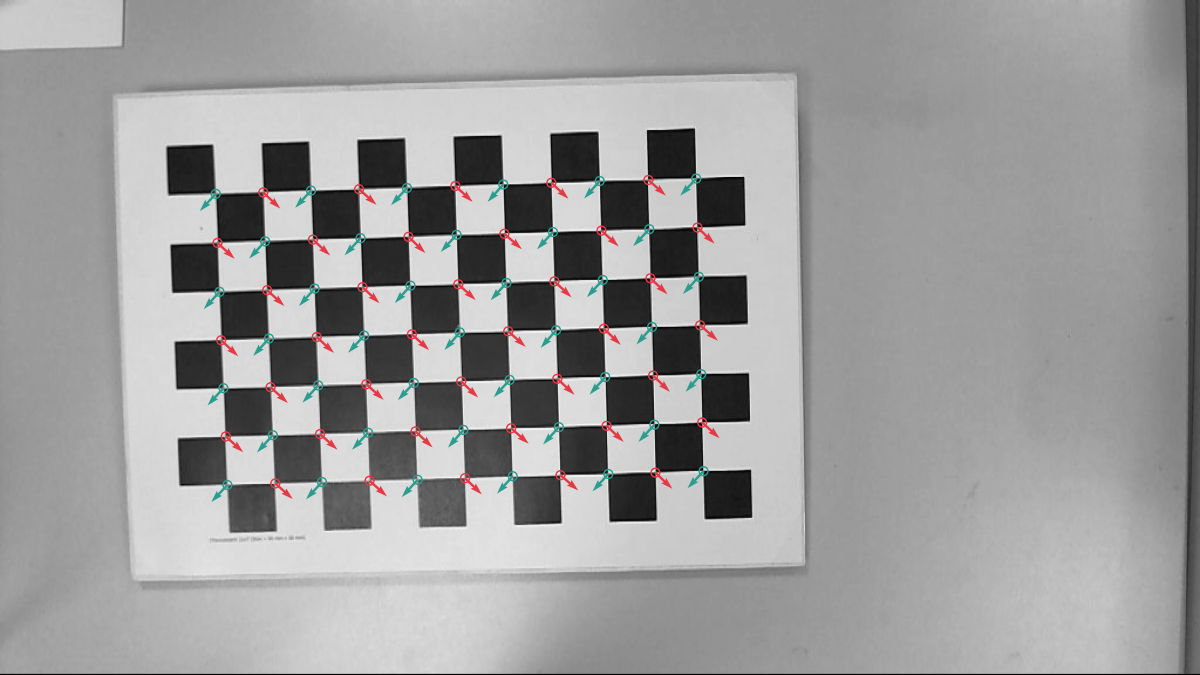

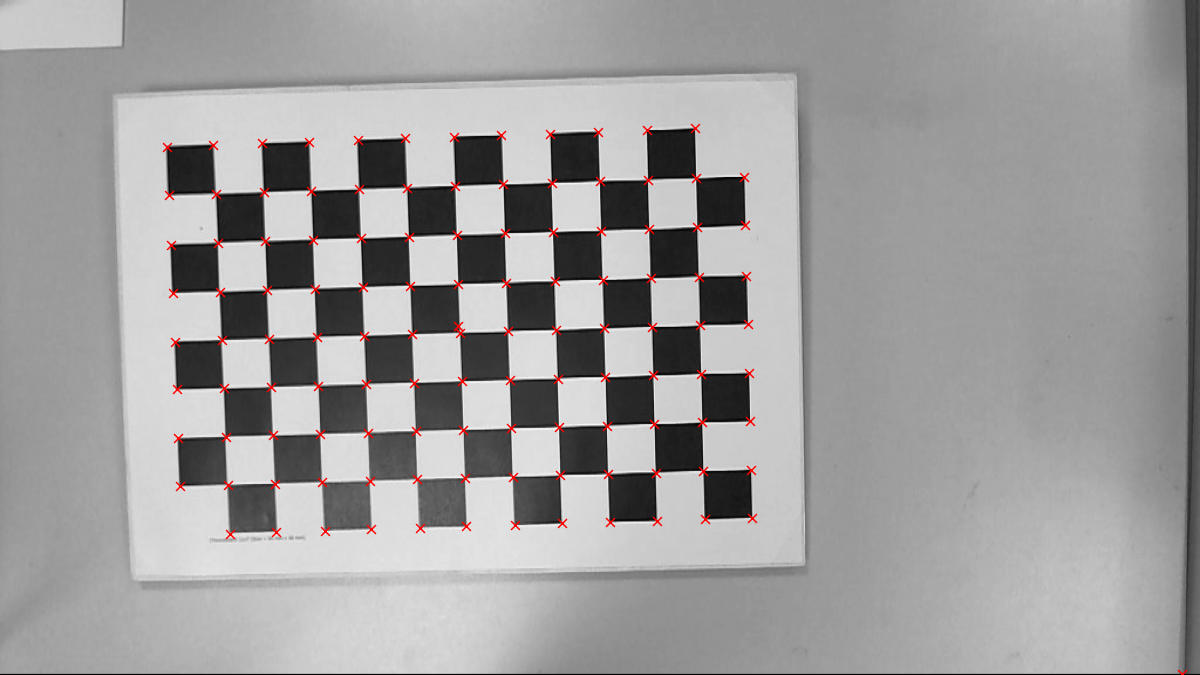

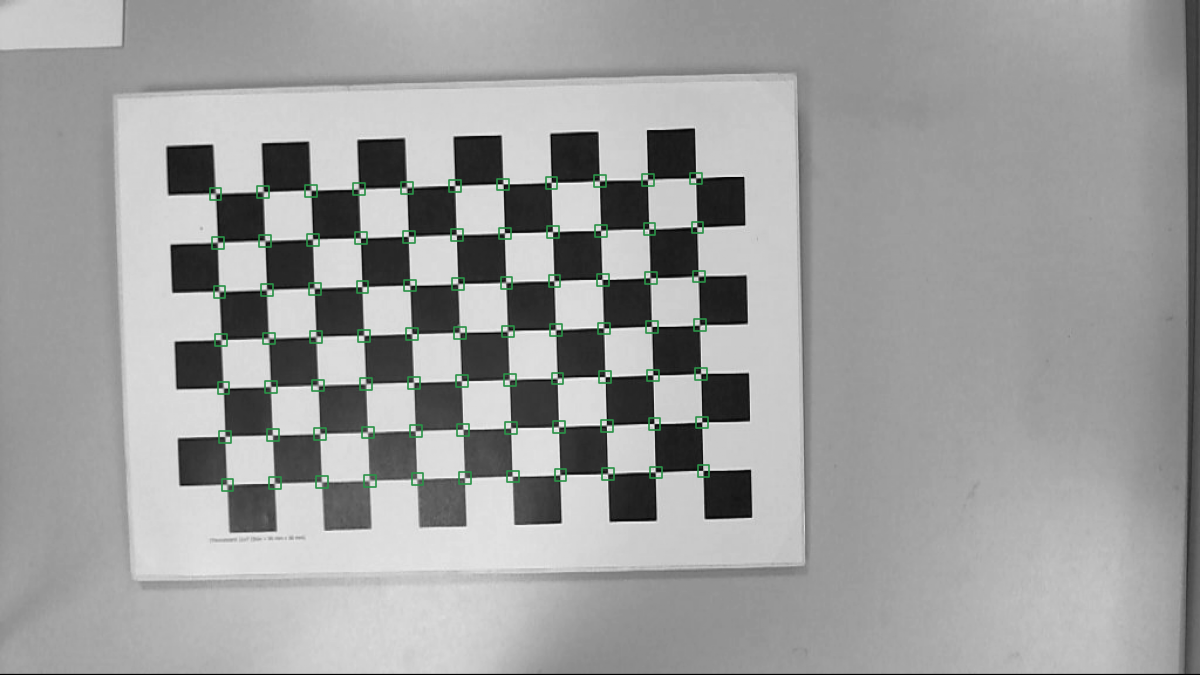

- A clear 1200x900 image of a chessboard calibration target:

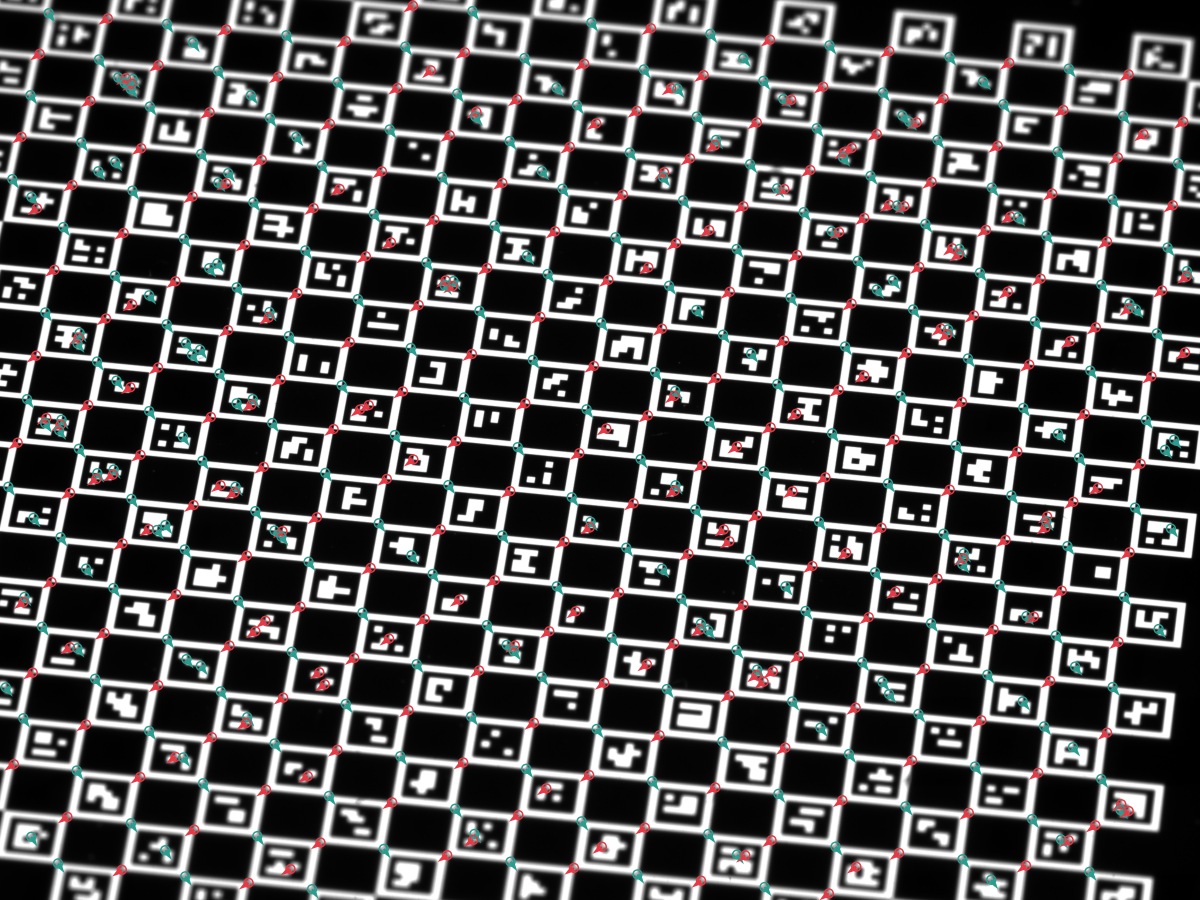

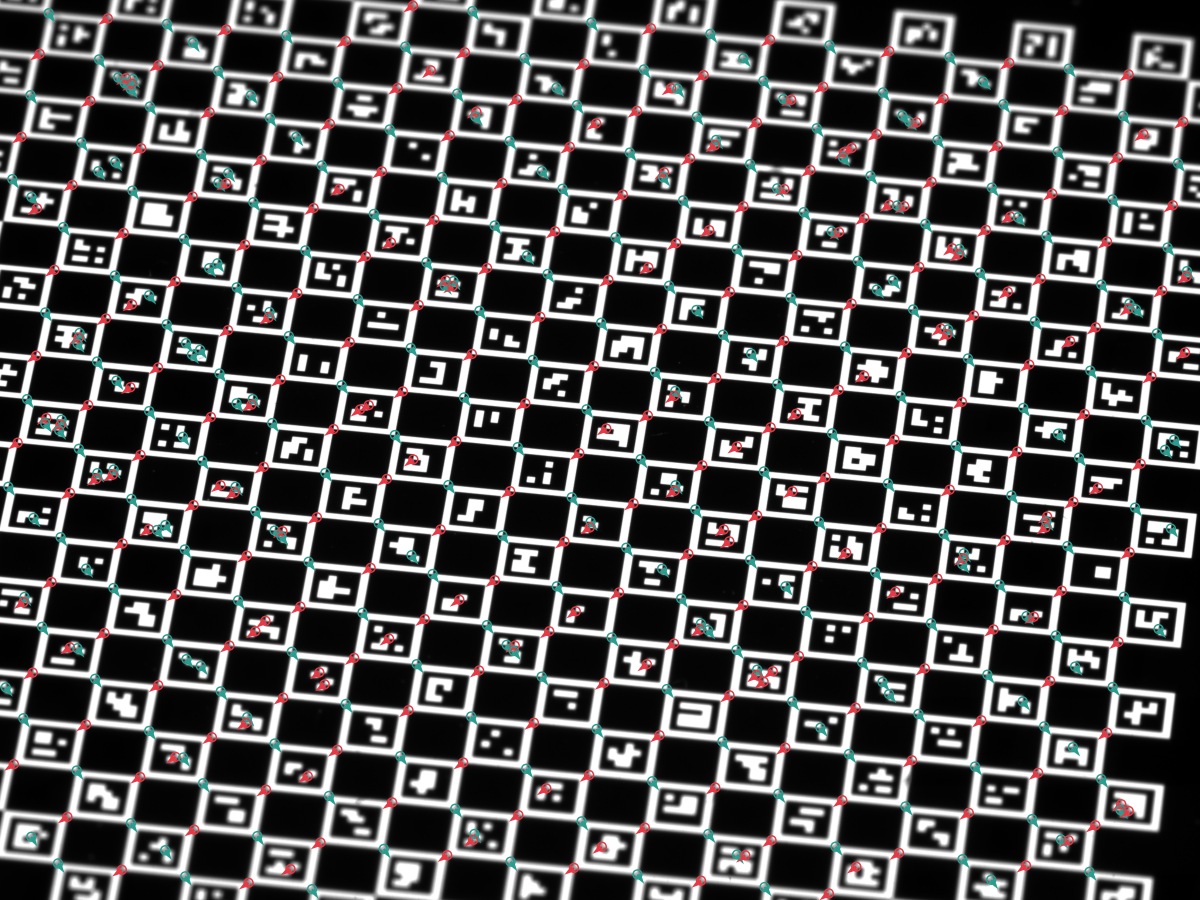

- A 720x540 image of a ChArUco target with not perfect focus:

- A 2048x1536 image of another ChArUco calibration target:

We traced the ChESS detector for each of these images, and the results are discussed in this part. The first image was also used to compare with OpenCV Harris features and the findChessboardCornersSB function. For accuracy, we additionally evaluated the detector on a 2×20‑frame stereo dataset (77 corners per frame).

5.1 Performance

The tests below were run on a MacBook Pro M4 (release build). Absolute numbers will vary on your hardware, but the relative behavior between configurations is quite stable.

Per‑image timings (ms, averaged over 10 runs; see book/src/perf.txt and testdata/out/perf_report.json for the full breakdown):

| Config | Features | small | mid | large |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single‑scale | none | 3.01 | 4.46 | 26.02 |

| Single‑scale | simd | 1.29 | 1.74 | 10.00 |

| Single‑scale | rayon | 1.14 | 1.41 | 6.63 |

| Single‑scale | simd+rayon | 0.92 | 1.15 | 5.34 |

| Multiscale (3 l) | none | 0.63 | 0.70 | 4.87 |

| Multiscale (3 l) | simd | 0.40 | 0.42 | 2.77 |

| Multiscale (3 l) | rayon | 0.48 | 0.52 | 1.94 |

| Multiscale (3 l) | simd+rayon | 0.49 | 0.54 | 1.59 |

Highlights from the timing profiles on small/mid/large images:

- Multiscale is the clear winner for speed and robustness.

- Large image: best total ≈ 1.6 ms with

simd+rayon(vs ≈4.9 ms with no features, ≈1.9 ms withrayononly). - Mid: best total ≈ 0.42 ms with

simdalone (rayon adds a bit of overhead at this size). - Small: best total ≈ 0.40 ms with

simd. - Breakdown: refine dominates (0.1–3 ms depending on seeds); coarse_detect sits around 0.08–0.75 ms; merge is negligible.

- Large image: best total ≈ 1.6 ms with

- Single-scale is slower across the board:

- Large: ≈26 ms, mid: ≈4.5 ms, small: ≈3.0 ms. Use when you need maximal stability and can tollerate some performance drawback.

- Feature guidance:

- Enable simd by default; it’s the dominant win on all sizes (although, it requires nightly RUST).

- Add rayon for large inputs (wins on the largest image, minor cost on small/mid).

5.2 Accuracy vs OpenCV

The OpenCV cornerHarris gives the following result:

Here is the result of the OpenCV findChessboardCornersSB function:

Harris pixel-level feature detection took 3.9 ms. The final result is obtained by using the cornerSubPix and manual merge of duplicates. Chessboard detection took about 115 ms. The ChESS detector is much faster as is evident from the previous section. Also, it provides corner orientation that can be handy for a grid reconstruction.

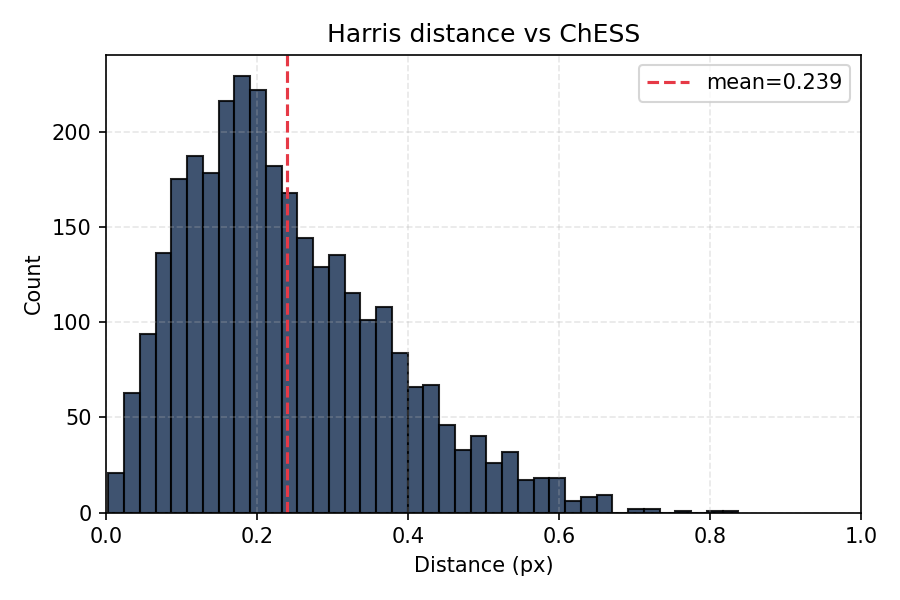

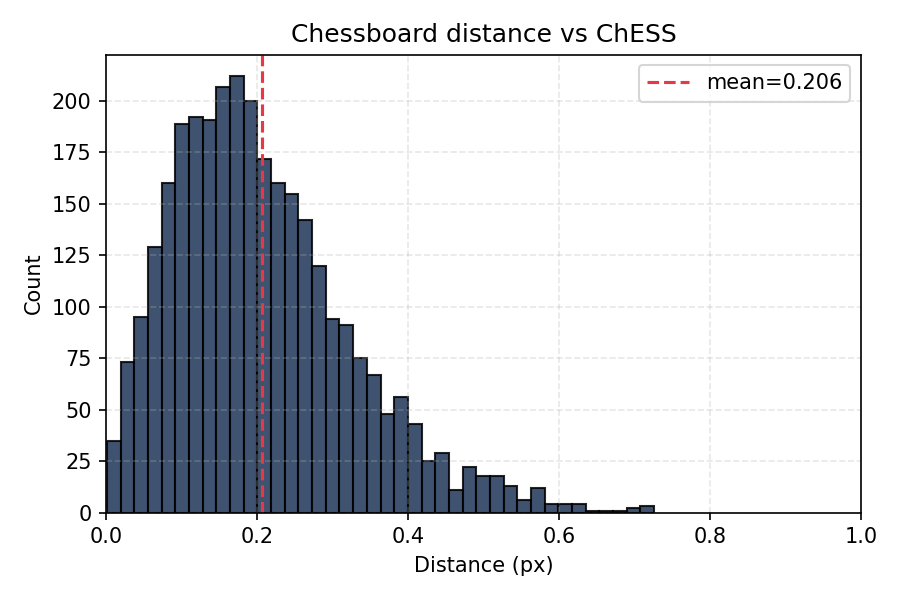

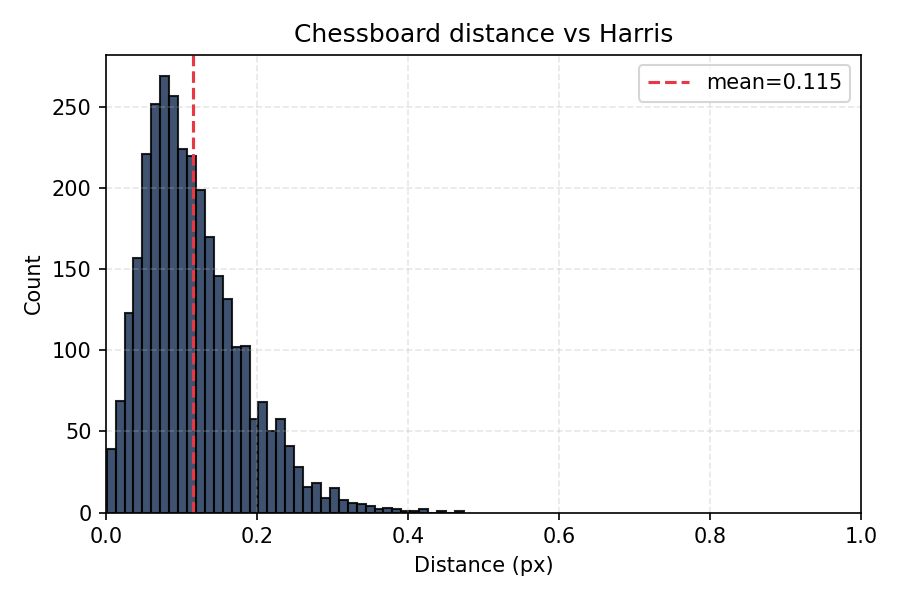

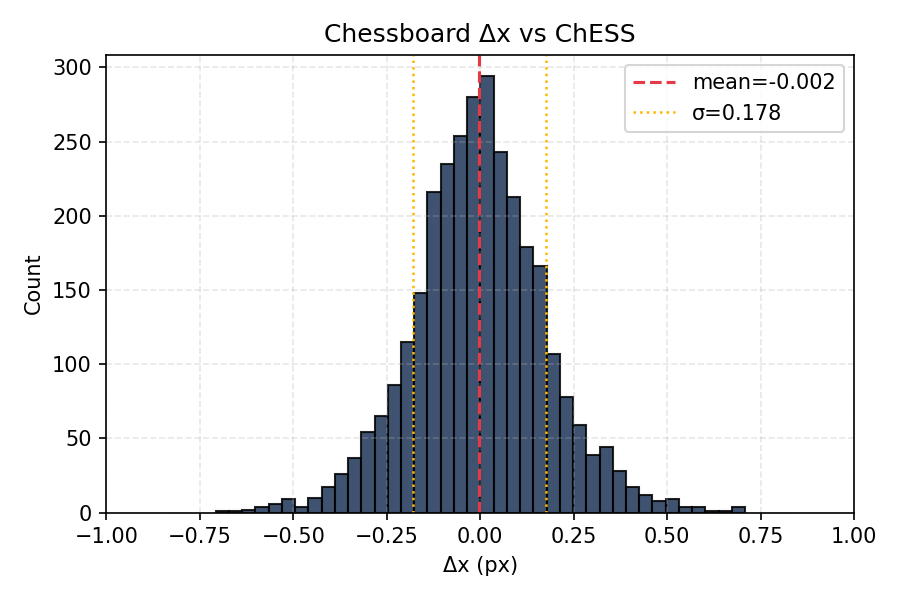

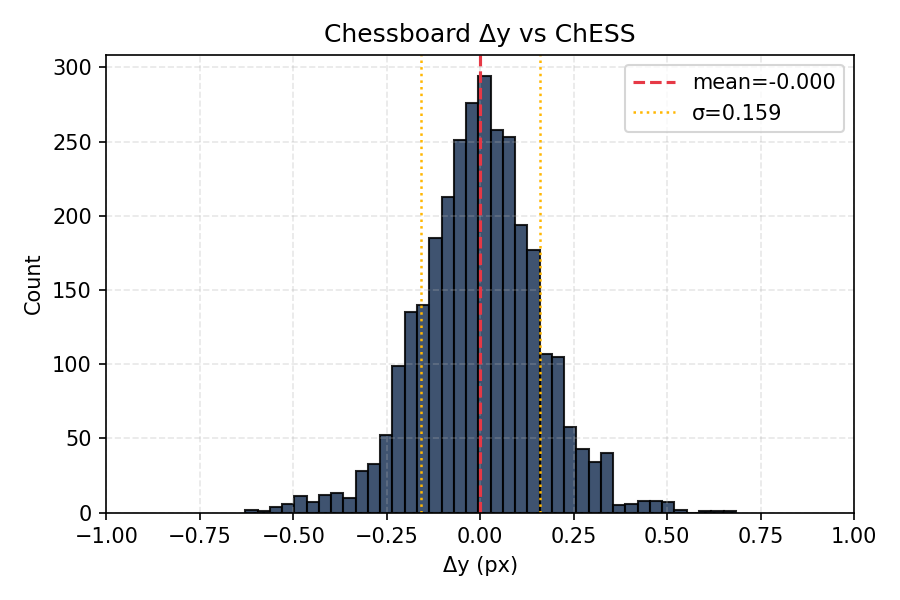

Below we compare the ChESS corners location with the two classical references. We took all images from the Chessboard Pictures for Stereocamera Calibration public repository as input. Below are distributions of pairwise distances between corresponding features:

- Harris vs ChESS: 0.24 pix

- Chessboard vs ChESS: 0.21 pix

- Harris vs Chessboard: 0.12 pix

It is important that the offsets are not biased:

Mean values are much smaller than standard deviation.

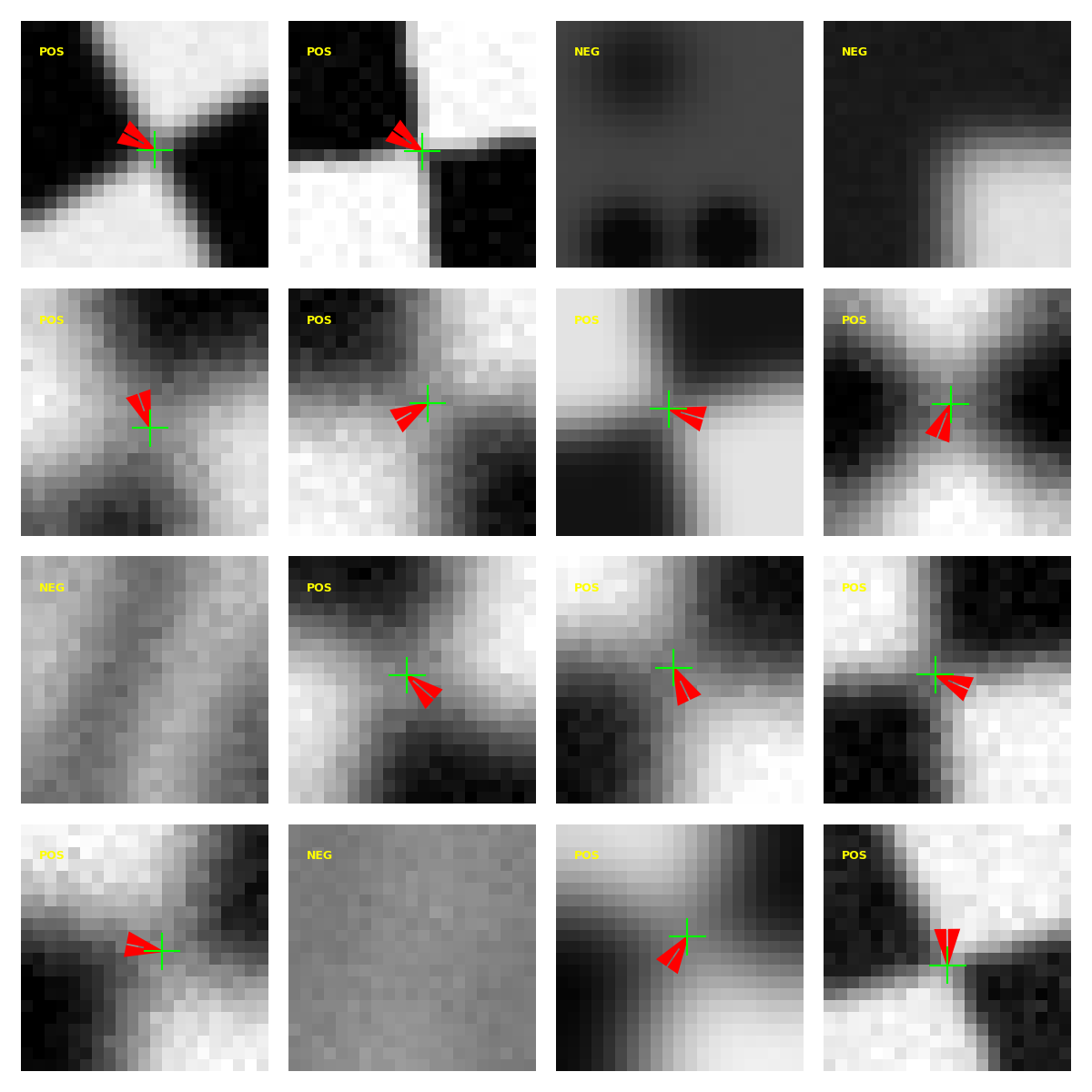

5.3 ML refiner (synthetic evaluation)

The ML refiner was trained and evaluated on synthetic corner patches

generated by the tooling under tools/ml_refiner:

The generator renders a

canonical chessboard corner, applies random homographies, blur, and noise, then

labels each patch with a subpixel offset (dx, dy) and a confidence score

derived from the distortion severity. The model predicts [dx, dy, conf_logit]

on normalized patches (uint8 / 255.0). The current Rust path ignores the

confidence output and applies offsets directly (confidence is used during

training/evaluation only).

Training and evaluation steps:

- Generate synthetic datasets with

tools/ml_refiner/synth/generate_dataset.py. - Train the refiner with

tools/ml_refiner/train.py(regression on positives, confidence on all samples). - Compare to OpenCV

cornerSubPixviatools/ml_refiner/eval/compare_opencv.py, which writes a JSON summary and plots for CDF and error vs noise/blur severity.

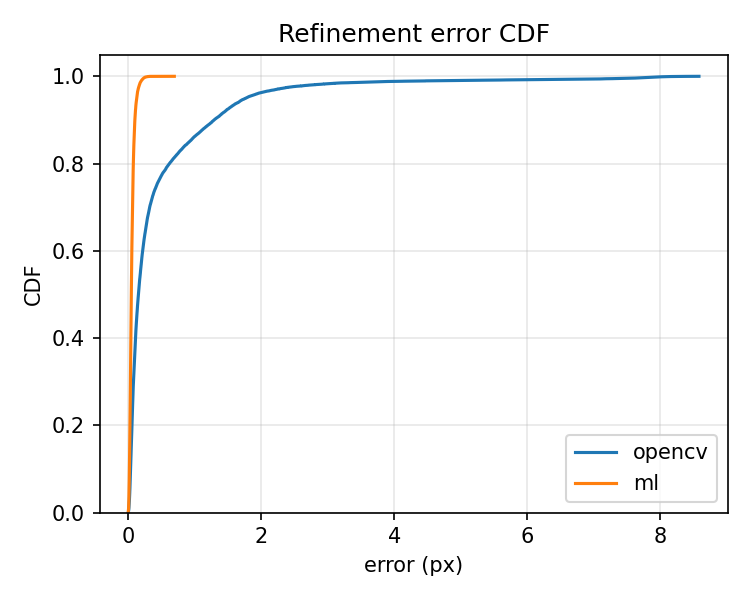

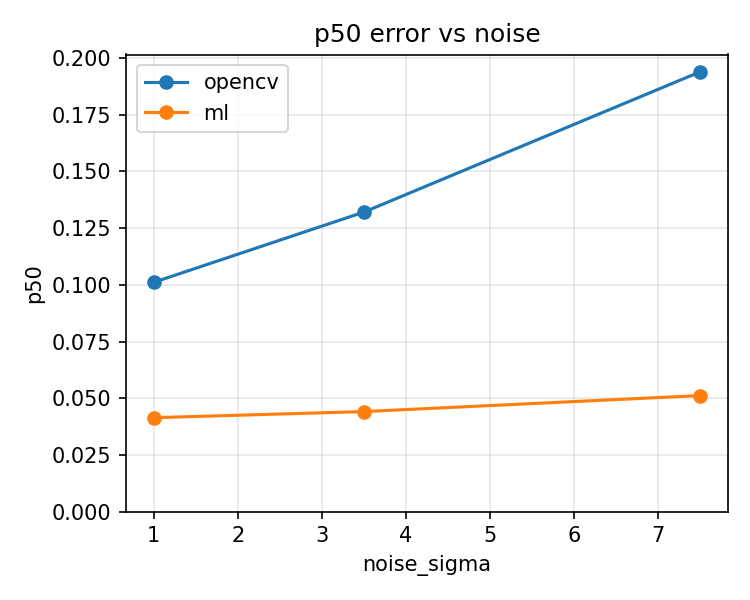

Updated results (synthetic data):

Numeric aggregates live in book/src/img/ml_summary.json (exported by the

evaluation scripts).

On this synthetic benchmark, the ML refiner shows substantially tighter error

distributions than OpenCV cornerSubPix, especially under noise and blur.

This does not yet guarantee real-world performance; realistic datasets still

need to be tested.

Timing note (single-scale on testimages/mid.png, 77 corners):

- Classic refinement: ~0.6 ms

- ML refinement: ~23.5 ms

The ML path trades speed for precision, so use it selectively (e.g., for off-line calibration or when accuracy is paramount).

5.4 Tracing and diagnostics

- Build with the

tracingfeature (the perf script does this) to emit INFO-level JSON spans. - Key spans now covered in both paths:

find_chess_corners(total)single_scale(single-path body)coarse_detect(coarse response + detection)refine(per-seed refinement, includesseedscount)merge(duplicate suppression)build_pyramid(pyramid construction)ml_refiner(ML refinement span + timing event when enabled)

- Parsing:

tools/trace/parser.pyextracts the spans above;perf_report.jsonis produced bytools/perf_bench.py, and accuracy overlays/timings come fromtools/accuracy_bench.py. - Use

--json-traceon the CLI (or run viaperf_bench.py) to capture traces; visualize or aggregate with your preferred JSON tools.

5.5 Integration patterns

- Real-time loops: reuse

PyramidBuffersviafind_chess_corners_buff; prefer multiscale + simd, add rayon for larger frames. Keepmerge_radiusmodest (2–3 px) to avoid duplicate corners without throwing away tight clusters. - Calibration/pose: the accuracy report shows sub-pixel consistency; feed detected corners directly into calibration routines. Use the accuracy histograms to validate new camera data.

- Diagnostics in the field: capture a short trace with

--json-traceand inspectrefine_seedsand span timings; spikes usually indicate harder scenes (more seeds) or contention (misconfigured features). - Reproducibility: keep generated reports under

testdata/out/; rerunaccuracy_bench.py --batchandperf_bench.pyafter algorithm or config changes, and drop updated plots into docs for before/after comparisons.

Part VI: Contributing and experimentation

The repository is intended to be a practical reference implementation rather than a one‑off experiment. If you are interested in contributing or using it as the basis for research:

- Bug reports and feature requests – if you run into issues on your own images or have feature ideas (e.g., better defaults, new configuration knobs), opening an issue with repro steps and sample data is extremely helpful.

- Testing and benchmarks – the Python helpers under

tools/and the data intestdata/are designed to make it easy to rerun accuracy and performance experiments after code changes. Extending these scripts or adding new datasets is a good way to validate improvements. - Algorithmic experiments – ChESS is only one point in the design space of chessboard detectors. Variants of the response kernel, alternative refinement strategies, or different multiscale schemes can all be explored while reusing the same benchmarking and visualization tools.

If you do build something interesting on top of this project—new bindings, specialized pipelines, or improved kernels—consider sharing it back so that other users can benefit and compare results on a common set of tools.